What is having low vision like?

Most likely, every depiction you’ve seen of what it’s like to have low vision…is misleading.

Whether it's a blurry filter, darkened edges or black blotches over a crystal-clear image, these depictions set the wrong expectations - and they can distort how you relate to someone with a visual impairment.

What Is Low Vision, Really?

“Low vision” is a term that often gets tossed around - and it can mean different things depending on who you ask.

Officially, it refers to someone whose best-corrected visual acuity is 20/70 or worse, or whose visual field is significantly restricted. But in practice, anyone with vision that’s “a little off” may get lumped into this category.

IMPORTANT TO REMEMBER:

Just because someone doesn’t meet the legal definition of low vision doesn’t mean their visual experience isn’t dramatically affected.

Why Simulated Images of Low Vision Are Misleading

Let’s talk about those visual simulations of conditions like macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy or hemianopia. They’re often inaccurate. Here’s why:

1. They use crystal-clear photographs.

Photos (and screens) show edge-to-edge clarity. That’s not how your eyes work.

In real life, you only see sharp detail in a small central zone - just 1–2° of your visual field. Everything else around that center is fuzzy and lower in resolution. So when an image shows a few black dots over an otherwise perfect photo, it gives the illusion that the person can just “look around” the problem. But that’s not possible - because...

2. The blind spot moves with the eyes.

In real vision loss, the missing or blurry part stays fixed relative to your gaze. If you move your eyes, the blind spot moves with you. You can’t “look past” it.

Misleading Images

Diabetic Retinopathy

Macular Degeneration

Hemianopia

So What Does Someone With Vision Loss Actually See?

Surprisingly, they often don’t see anything missing at all. They don’t see black spots. They don’t see blur. They just don’t see.

Why? Because the brain fills in the blanks.

Visual information is processed in the back of the eye (the retina) and sent down the optic nerve to the brain. If part of that information is missing, your brain:

- Doesn’t alert you

- Doesn’t create a black hole

- Just fills in with what it thinks should be there

EXAMPLE: YOUR NATURAL BLIND SPOT

Every eye has one spot where the optic nerve exits the retina -no photoreceptors there, no sight. But you don’t notice it. Your brain just fills it in.

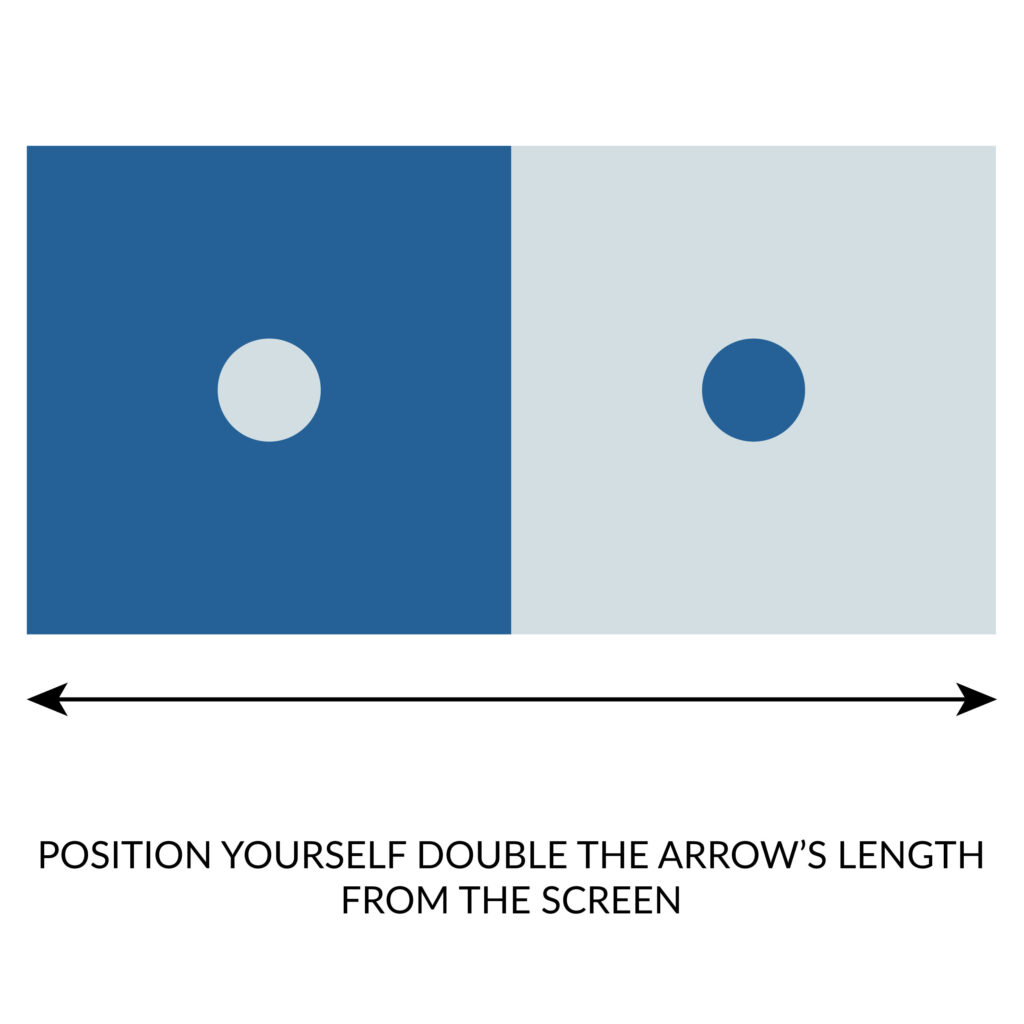

Test Your Blind Spot

Try this:

- Position yourself double the arrow's length from the screen

- Close your left eye.

- Look at the left dot on the image with your right eye.

- Move closer or farther until the right dot vanishes.

That's your physiological blind spot - the spot where your optic nerve enters the retina. You don’t see it in daily life, because your brain fills it in.

Why Many People Don’t Know They’ve Lost Vision

Because the brain is so good at covering for the eye, someone could lose:

- Half their vision

- Almost all of their peripheral vision

- Major parts of their central vision

…and not even notice.

That’s why many vision impairments go undiagnosed for too long.

Charles Bonnet Syndrome: Seeing What Isn’t There

If someone has significant vision loss, they may begin to see things that don’t exist. This is called Charles Bonnet Syndrome. It’s like phantom limb syndrome for the eyes.

When the brain isn’t getting normal visual input, it may invent images - faces, shapes, figures, even entire scenes - to fill in the silence.

These hallucinations:

- Are not a sign of mental illness

- Are more common than most realize

- Can be scary or confusing for those who don’t know what’s happening

If a patient describes “seeing things,” don’t dismiss it. They may be experiencing a real, known neurological response to vision loss.

The Bottom Line

Vision loss isn’t just “blur” or “darkness” or “black spots.” It’s subtle. It’s sneaky. And it’s different for every individual.

So next time you see an overly dramatized simulation of low vision, remember:

- Real vision is not like a photograph

- Missing vision doesn’t always feel “missing”

- People with vision loss often need understanding more than assumptions