The Eye & Brain Connection

The Journey From What We See to How We See It

Our eyes, like every other part of our body, connect to the brain. In fact, there is a literal line from the eyeballs to the brain, and that line is known as the optic nerve. But while that connection seems simple and straightforward, it is NEITHER simple NOR straightforward. That’s why you can have what is considered perfect eyesight (20/20) and still have vision problems.

To understand how, we need to look at:

- How the eyes and brain connect structurally

- How the eyes and brain connect in terms of information processing

- What the brain does with that information

As humans, we rely predominantly on our sense of sight to understand the world around us. What we see with our eyes is 100% affected by and reliant upon how our brain processes the images we take in. What makes diagnosing certain vision issues challenging is that, while you may be able to see 20/20 (meaning you can see and read a street sign from 30 feet away), the energy you are using to simply get your brain to process that information correctly is exhausting and can leave you feeling very frustrated. It is very likely that somewhere between your eyeballs and your brain, something went wrong.

If there is a disconnect, what we see and what we think we see don’t match up. Not only is that disorienting in a cognitive way, disrupting our ability to ‘trust what we see’, but it can also create other physical issues.

Nitty-Gritty Science

The eyes are like a direct line into our brain health. They provide insight into issues happening neurologically as well as optically.

Structurally, the eyes and brain are a team, whereby ‘multiple parallels can be drawn between their neurons, vasculature, and immune response. Furthermore, both organs modify similarly with disease.1 Here’s how they work together.

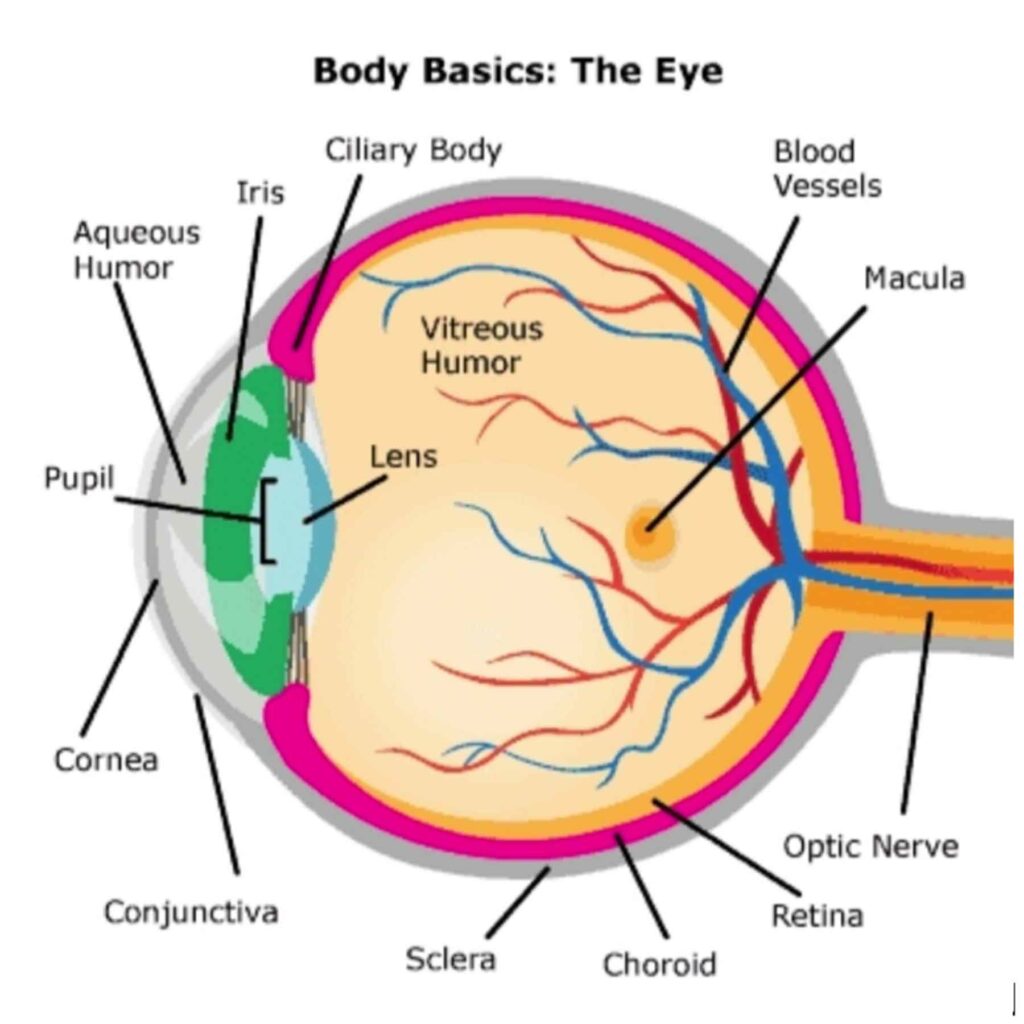

This is your eye, in all its globular glory.

When we detect an image, light reflected off the image travels into our eyes in the form of light receptors (AKA rods and cones) to our retina (the layer at the back of our eyes that is light sensitive). The retina receives the light signals and processes them, but in what seems a convoluted way. The signals are processed upside down and flipped. Kind of like how we see our reflection in a mirror.

In a properly functioning system, each eye has corresponding optic nerves, little cables of nerve fibers made up of a collection of neuronal axons, which are the points of connection between the retina and the brain. The retina uses those optic nerves to send signals to the brain. But instead of sending what the right eye saw to the right side of the brain and what the left eye saw to the left side of the brain, the retina shakes things up. Or, more specifically, a few of the axons change course.

The signals may START OUT on the straight and narrow, with signals from the right eye going to the right side of the brain and signals from the left side going to the left side of the brain. But about midway through their journey, some of the axons change course at a point called the optic chiasm. Big word, we know. Now, some of what came in through the right eye is going into the left side of the brain, and some of what came in through the left eye is headed towards the right side of the brain. Why, optic nerves, why? Oh, and when they shift lanes, they are no longer called optic nerves, but optic tracts.

Despite seeming completely nonsensical, it turns out this is a good thing because those axons that took the road less traveled enable us to have greater depth perception. One of many evolutionary tactics that prevents most humans from just walking off cliffs. There’s more to it, though...

The optic tracts don’t send their messages directly to the brain. They take a pitstop in a region of the brain called the thalamus, where they dump what they’re carrying into the lateral geniculate nucleus (or LGN) and say ‘Adios.’ Now it’s incumbent upon the LGN to relay the info to its destination. The LGN is incredibly important because this is where the body integrates visual data with the rest of the senses and translates abilities like balance. Have you ever tried to stand on one leg with your eyes closed? Hard, isn’t it? It’s not because you can’t “see”, it’s because the information your brain uses to “balance” is missing.

Then the brain (or, more specifically, the visual cortex of the brain) takes that mass of information, processes it, and creates a coherent picture with it, turning elements like light, color, shape, and shadow into something meaningful that makes sense of what’s before us.

Once we process what we are seeing, we can then react appropriately to it. Of course, this happens at lightning speed, so we don’t even notice it happening. Unless, of course, it isn’t happening, or it is happening in an unusual way.

The Vision Express

Now that we have the physical structure down, we need to take it a step further and understand the eye-brain connection with regards to how we process what we see. It’s a complicated relationship.

A good way to think of it is to imagine our vision as a bus on its way from Point A to Point B. The information the eyes take in through the sense of sight are the passengers. The roads that bus travels on are the nerves connecting the eye to the brain. And the brain is the final destination where everything eventually ends up – essentially, the transportation terminal.

The brain is where everything our senses take in gets named, checked in, and catalogued. It’s where the body interprets and makes sense of what it sees and decides what to do with that new information. It then puts those passengers (new information) on other buses and sends them to other parts of the body, where we react accordingly based on whether what the brain perceives the eyes are seeing is considered a threat or not.

In the brain, sight becomes vision, and we attach meaning to the information coming in on the bus. It's where we make sense of it and respond.

Under normal circumstances, the eyes (bus) will pick up a passenger (information) and carry it down the road (nerve) to the transportation terminal (the brain).

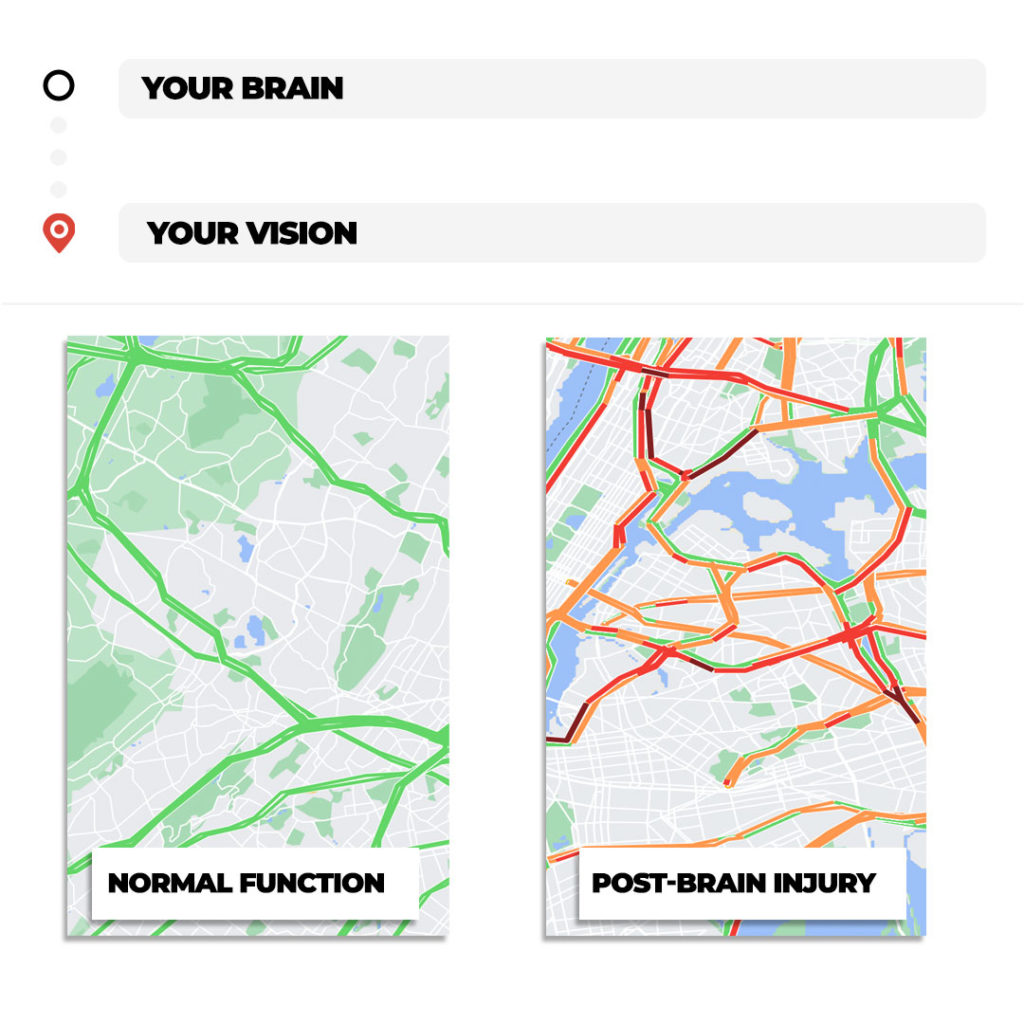

Now, when there is an issue with the connection between the eyes and brain, that bus may end up on the wrong route, drive off a cliff, head in the wrong direction, or drop its passengers off at the wrong locations. The result is that we don’t process what we see correctly, so our brain doesn’t respond appropriately and is sending those “passengers” off with the wrong messages.

That messes with our vision because if the message going into the brain is incorrect to begin with, or if the channels between the eyes and brain are broken or scrambled, the message going out from the brain will be incorrect as well. Which means we might not react as we should. Or we might not even react at all. Which is, of course, not good.

How It Can Go Haywire

According to Brainline, ‘40-50 percent of the brain is involved in vision; so, if a person’s brain is damaged, say by a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), in a specific location or several locations, there is a high probability that his/her vision will be affected in some way.’ Additionally, ‘for TBI’s in general, the literature says 20-40 percent of people with brain injury experience related vision disorders.’

Basically, if there’s a problem with that connection between the eyes and brain, things do not get put back together again, or at least they don’t in a way that makes any sense. So, you get a jumble of colors, shapes, and shadows that are hard to interpret, kind of like Picasso in his cubist period. That translates to being unable to adequately make sense of what you’re seeing, which further means you might not react appropriately.

Best case scenario? Your impaired vision could simply result in you doing some embarrassing faux pas. Worst case scenario? Your impaired vision could cause you to do something legitimately life-threatening to yourself and/or others.

You need to get to the root of where vision problems may be coming from, and those problems don’t always begin with the eyes. Sometimes, the problems originate in the brain. And while your vision might register as 20/20 on an eye exam, your friendly neighborhood brain knows better. There’s more to being able to see correctly than reading some tiny letters on a piece of paper at the end of the hall, and HOW you see is just as important and WHAT you see (or don’t see).

You may THINK you are going crazy, but it’s really a disruption in the critical eye to brain connection.

Sources:

- (‘Seeing Beyond the Eye: The Brain Connection’, Nguyen, Christine T. O.; Acosta, Monica L.; Di Angelantonio, Silvia; and Salt, Thomas E. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.719717/full)

- (The Mind’s Machine, Foundations of Brain and Behavior (Second Edition), Watson, Neil V., and Breedlove, S. Marc (https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2012-08917-000)